For more than a decade before the outbreak of the American Revolution, the marriage between Great Britain and her English Colonies in America was in crisis. The Stamp Act, Townshend Acts and Tea Act were all triggers for English Colonists, who, as emigrants of the Crown, still somehow wanted all the same perks and homecourt advantages of home.

The Boston Tea Party and Massacre led to the Coercive Acts, and in response a group of thought leaders including George Washington, John Adams and others met in Philadelphia to levy their grievances to the Crown. In their “Declarations and Resolves of the First Continental Congress” they outlined 12 talking points which began:

October 14, 1774—The inhabitants of the English Colonies in North America, by the immutable laws of nature, have the following RIGHTS:

Resolved, N.C.D. 1. We are entitled to Life, Liberty, and Property.

It was the first time that particular phrase appeared in American nomenclature, and, in addition to building out their original 13 Colonies, America’s founders and future leaders were tasked with creating marriage laws, too.

While states draft and regulate their own marriage laws, each unique in their own particular way, there are 1,138 federal statutes that oversee the nation’s marriages in terms of benefits, rights and privileges, according to the United States Government Accountability Office.

Considered a “fundamental right” by the U.S. Supreme Court in 15 different opinions, the federal government now intercedes to legislate the affairs of married, divorced, even widowed spouses on everything from social security > pensions > survivor benefits > tax-free transfers > and income tax. But is the federal government’s oversight rewriting state marriage laws?

The 1996 Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) prohibited the federal government from recognizing same-sex couples who were lawfully married in their state. A conflict between DOMA and the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment led the U.S. Supreme Court to rule DOMA unconstitutional (United States v. Windsor). Moreover, its precipitated and ultimately legalized same-sex marriage as the law of the land (Obergefell v. Hodges).

When women married in Colonial America, they had rights but no autonomy. They found themselves in positions of almost total dependency on their husbands which the law called “coverture.” English jurist William Blackstone describes the legal atmosphere of marriage in 1765 in the “Commentaries on English Law:”

By marriage, the husband and wife are one person in the law: that is, the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage, or at least is incorporated and consolidated into that of the husband: under whose wing, protection and cover she performs.

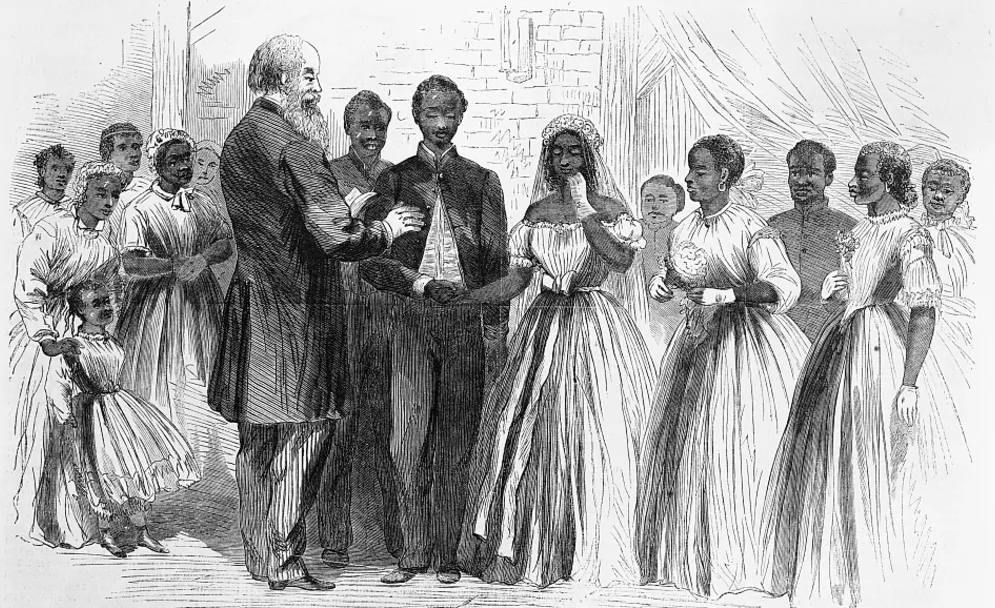

While the Thirteenth Amendment emancipated the slaves, it was the subsequent Civil Rights Act of 1866 that acknowledged their right to marry.

After emancipation, freed people were permitted to make their unions legal by applying to their state for marriage licenses. On March 3, 1865, an Act of Congress established the Freedmen’s Bureau and published an announcement in a politically progressive biweekly magazine called "The Nation:"

Any couple who appears before a Justice of the Peace, or Clerk of the Court, and states when they began living together as husband and wife, will be issued a certificate and considered lawfully married, retroactively.

The Freedmen Bureau, Harpers Weekly 1866

A scant 50+ years on, the same latitude would apply to common law marriages, too. The Nineteenth Amendment granted women the right to vote in 1920; triggering a cacophony of supreme court legislation on everything from birth control (Griswold v. Connecticut), interracial marriage (Loving v. Virginia) and abortion (Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization). The Woman’s Rights Movement was a fearless march toward equality, and suffragist Susan B. Anthony spoke with unequivocal clarity:

The true republic: men, their rights and nothing more.

Woman, their rights, and nothing less.

By the 21st century, even the gays were getting married (Obergefell v. Hodges), polygamy was passé (Edmunds Act), and sodomy was all the rage (Lawrence v. Texas). The Supreme Court based their ruling on the notions of a) personal autonomy to define one's own relationships, and b) the traditions of non-interference with private sexual decisions between consenting adults. The states, it seems, were having their say but the federal government was the American way.

The Kingdom of Great Britain’s “An Act for the Better Preventing of Clandestine Marriage” in 1753 was the first statutory legislation for marriages in England. It set the legal age to marry at 21, required a church service, and a receipt; a formal certificate of marriage had to be issued by His Majesty’s government.

Heretofore, marriage was merely a religious ceremony. The only requirement for a valid marriage in England and Wales was directed by canon law and the Church of England. However, the “Clandestine Marriage Act” now required marriages to be registered with the county clerk, administered by the state, effectively licensing and in due course taxing the couple's personal relationship.

It was an attempt to intercept young English couples from eloping to a boarder Scottish town, Gretna Green; where the legal age to marry was 14 for boys, 12 for girls. While Scottish law recommended a marriage license be obtained before a marriage, and the Church of Scotland proposed it take place in a parish, these were suggestions, not requirements, for young couples even Jane Austin envisioned at the anvil and the Blacksmith's Shop.

Gretna Green Scotland

While eloping to Scotland was threatening power and property structures in England, questions about where and how to marry became urgent matters of public debate in Parliament. In the same year, in an unprecedented marriage of church and state, Lord Chancellor Hardwicke required all weddings to be legally solemnized in an Anglican church.

Clergymen who defiled the Clandestine Marriage Act were pilloried, had their ears cropped, and were imprisoned, fined and deported until the Act was at length repealed in 1849. But the construction of a toll road, passing through and hitherto an obscure village of Graitney, gave access to Gretna Green for those 100 years. Where star-crossed lovers have and continue to say “I do.”

Archives